The men’s

health gap

When it comes to health, statistics show us that men are the weaker sex, even when it comes to the current pandemic. Men are more likely to die from COVID-19 - around 1% more likely than women.

But where is the men’s health gap the largest? And do any countries buck this trend and have

healthier men than women?

What is a health gap?

Health gaps are differences in the prevalence of disease, health outcomes (both physical and mental), or access to healthcare

across

different groups. These groups can be anything from ethnic to socio-economic. In this study we have

examined

the health gap by gender across 156 countries around the world.

In most countries, men are in more positions of power, have more privilege and more wealth than women.

However, all this advantage doesn’t necessarily translate into better health. We see this in a number of

outcomes, across both physical and mental health.

The mental health gap

Even before the current pandemic, significant care deficits in mental health were unfortunately commonplace. Gender played a role in risk factors associated with different mental health issues.

According to a recent study in The Lancet, on top of this existing pressure, the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted the delivery of mental health services. The psychosocial burden of lockdowns, job losses and deaths of loved ones will likely become evident in the coming months.

It’s also likely that women and men will experience and respond to these triggers differently. Men are more likely to experience substance abuse and suicide is the biggest killer of men under 50. But women are twice as likely to be diagnosed with anxiety and depression is more common in women too.

Our study’s findings highlight which nations could see the largest surges in mental health cases as we enter the next stage of the pandemic.

New Zealanders are most at risk. The most recent New Zealand Health Survey found that 8% of adults had experienced psychological distress in the past four weeks, up from 4.5% in 2011/12. Those from Māori and Pacific heritage are more likely to experience mental health problems than the rest of the population too.

New Zealand’s response to the pandemic has been widely praised. But with lockdown measures expected to be lifted ahead of schedule, it could be the first country to feel the full mental health effects.

Which countries have the largest male health gaps?

A male health gap is when women are generally healthier across their lives than men. Eastern European

countries dominate this category, with Georgia taking the unwelcome prize of the largest male health

gap.

There are 84 positions between its rankings across men’s and women’s health categories.

A previous study by WHO found that men were less healthy

in

countries where levels of gender inequality are high. Georgia and the rest of the Eastern European

countries

are traditionally patriarchal societies.

The study suggests that health risks from smoking, alcohol and substance abuse (where these countries

score

particularly poorly) are linked to cultures that embrace stereotypical ideas of masculinity.

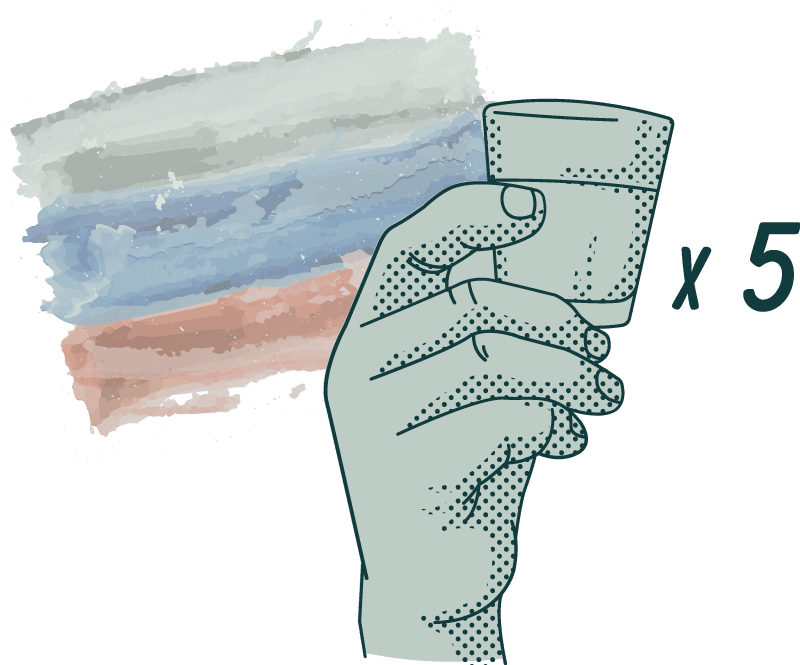

A study of men in the Russian Federation suggested that heavy

drinking

elevates or maintains a man’s social standing. This is because of the cultural masculine ideal of “the

real

working man”. So, Russian men don’t drink more because they’re men, but because of the social pressures

on

them to do so.

Russian men drink an average of 66 grams of pure alcohol a day, equivalent to nearly five measures of vodka.

For many men, work is central to their masculinity. The position of the man as the main earner of the

family

is key to the patriarchal model. Despite this perpetuating male power structures, it has been shown to

be

detrimental to men’s health.

The role of breadwinner was found to be a risk factor for

heart attacks and chronic back pain.

Research has also suggested a link between men working more hours (as the breadwinner) and

higher blood pressure and increased levels of smoking.

Which countries have the largest female health gaps?

Unexpectedly, there are countries that don’t follow the trend of men being unhealthier throughout their

lives. These countries therefore have female health gaps; where their rank for women’s health is lower

than

their rank for men’s health.

The Netherlands has the largest female health gap, with its rank for women’s health 62 places lower than

that for men’s health. Other nominally progressive countries such as Norway (57 places), Sweden and

Denmark

(both 48 places), and the UK (38 places) have large women’s health gaps.

This gender gap seems to be for a variety of reasons. One part is the misdiagnosis of women’s symptoms.

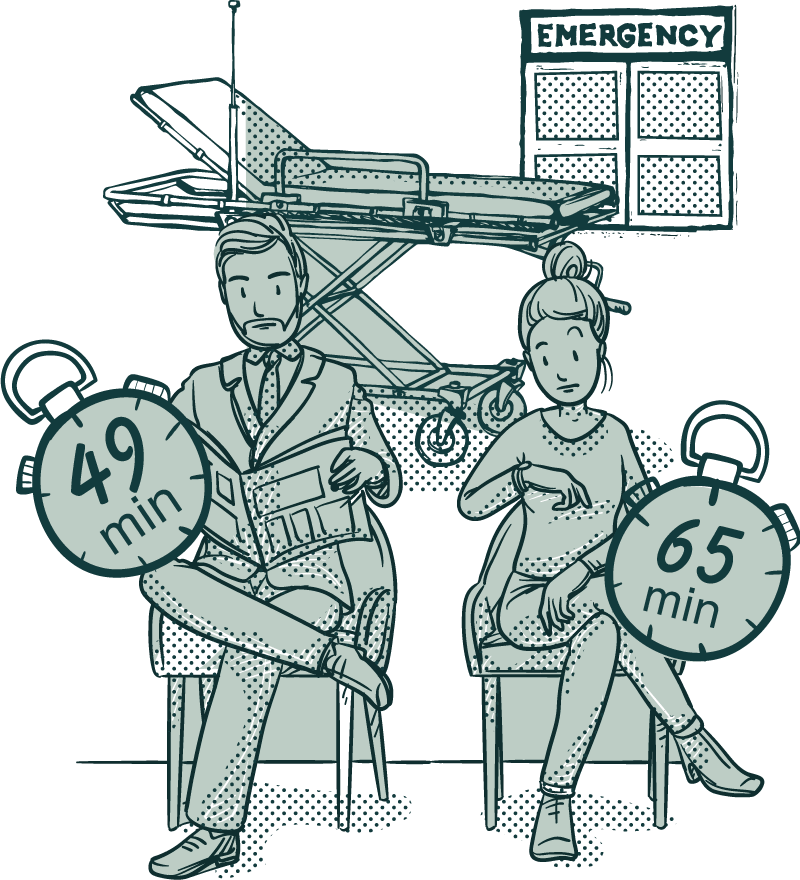

Women wait an average of 65 minutes to be seen by a doctor in A&E. Men only wait 49 minutes.

A study of men and women who went to A&E with abdominal pain showed that women

waited an average of 65 minutes to be seen by a doctor. Men only waited 49 minutes. And the

women

were less likely to be given painkillers too.

In another example, women tend to have better verbal memories than men. This means they perform better

in

memory tests, and so early stage Alzheimer’s is

less likely to be diagnosed.

The disease is therefore more likely to be serious when diagnosed, leading to deterioration more

quickly.

Another reason for a women’s health gap is that their health concerns are just not taken as seriously.

Research by Oxford University found that

women are 13 per cent less likely than men of the same age to

receive

life-saving drugs such as statins after a heart attack. This may be one reason

women are twice as likely as men to die in the 30 days

after

a heart attack.

Finally, women’s bodies, and the conditions that affect them, are less likely to have been medically

studied. In a form of observer bias, male clinicians are more likely to study men. Even male lab rats

are

used instead of female ones. And after the thalidomide scandal, women “of childbearing potential” were

banned from clinical trials

between 1977 and 1994.

This attitude can still be seen today. One 2015

study into a “female Viagra” included 25 participants. 23 of these were men.

Conclusion

We started this study expecting to find evidence of widespread inequality between men’s and women’s

health.

While this was indeed what we found, the actual results surprised us.

Just as there are countries where men are less healthy than women, so too are there countries where the

opposite is true. This is clearly for a variety of reasons.

Male health gaps seem to stem from societal pressures that are damaging men the world over. Traditional

masculinity is quite literally toxic.

And female health gaps are proof that patriarchy can afford men better healthcare. Women are less

studied,

misdiagnosed, and taken less seriously by the health system.

Therefore, men and women must work together to combat health inequalities. Input is needed from all

levels

of society, from private citizens to educators, medical professionals to lawmakers.

This is just one part of the greater struggle against worldwide gender inequality. A more equal society

improves the health of everyone involved.

Dr. Earim Chaudry, Medical Director at Manual commented on the findings:

“It really is eye-opening to see the differences between genders when it comes to health and to explore how the COVID-19 pandemic could escalate these figures.

Governments and healthcare providers must carefully plan for the next phase of the coronavirus pandemic and allocate sufficient resources to ensure a high standard of care.

Everyone, no matter their gender, age or background, should own their health and happiness by accessing the support available to them and speaking to a medical professional as soon as symptoms appear.

”